The demographics of your organisation determine the distribution of knowledge, and therefore the details of the Knowledge Management Framework you need to deploy

Here's another factor that can affect the way you address KM in an organisation; the demographics of the workforce.

Because the demographics are is linked to the distribution of knowledge across the staff, it determines how many sources of knowledge you have, how many net users, and the balance between the two.

For example:

An organisation with many experienced staff.

This is a profile you see in many Western engineering organisations. Here the economy is static, and the population growth is stable. Engineering is not a "sexy topic". The workforce is largely made up of baby boomers. A large proportion of the workforce is over 40, with many staff approaching retirement - the blue line in the graph above.

Experience is widespread in the organisation - this is an experienced company, and knowledge is dispersed. Communities of Practice are important, where people can ask each other for advice, and that advice is spread round the organisation. Experienced staff collaborate to create new knowledge out of their shared expertise. Knowledge can easily be kept largely tacit. The engineers know the basics, and a short call to their colleagues fills in any gaps. The biggest risk is knowledge loss, as so many of the workforce will retire soon, and a Knowledge Retention strategy would be a good investment.

An organisation with many inexperienced staff

In many parts of the world, such as the BRIC countries, the economy is growing, the population is growing, there is a hunger for prosperity, and engineering (in contrast to the West) may be a growth area. The workforce in a growing organisation may be predominantly very young - many of them fewer than 2 years in post. There are only a handful of real experts, and a host of inexperienced staff - the red line in the chart above.

Experience is a rare commodity, and is centralised within the company, retained within the Centres of Excellence, and the small Expert groups. Here the issue is not Collaboration, but rapid onboarding and upskilling. The risk is not so much Retention of knowledge (although of course the knowledge of the few experts is vital and must be protected), but is more about deployment of knowledge. The reliance on a few experts means that they must be given a Knowledge Ownership role, rather than using them on projects. Rather than keeping knowledge tacit, it makes sense to at least document the basics in explicit form (the experts will be too busy to answer basic questions), though there is of course a need to keep this documentation updated as the organisation learns.

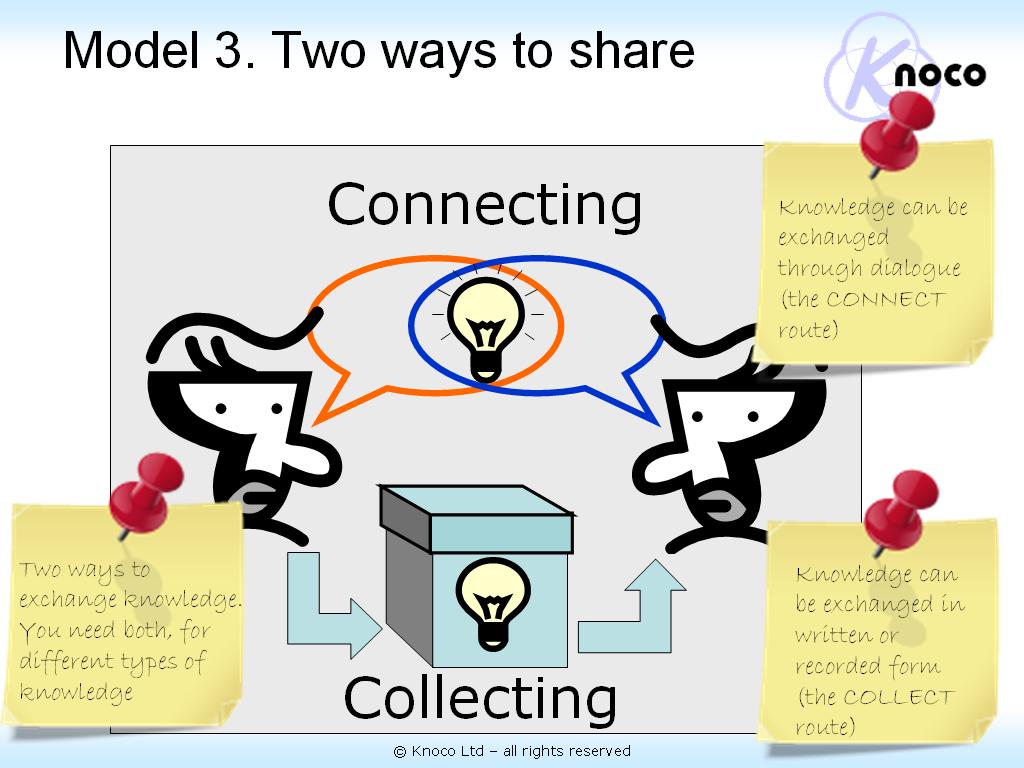

- A company with very many experienced staff will have many knowledge suppliers, each of whom is also a knowledge user, and will therefore have to find an efficient and effective way to allow these people to compare, combine and continuously improve the knowledge they have.

- A company with very many junior staff and few experienced staff will have few knowledge suppliers and many knowledge users, and will therefore have to find an efficient and effective way to provide the knowledge of the few, to the many.

An organisation with many experienced staff.

This is a profile you see in many Western engineering organisations. Here the economy is static, and the population growth is stable. Engineering is not a "sexy topic". The workforce is largely made up of baby boomers. A large proportion of the workforce is over 40, with many staff approaching retirement - the blue line in the graph above.

Experience is widespread in the organisation - this is an experienced company, and knowledge is dispersed. Communities of Practice are important, where people can ask each other for advice, and that advice is spread round the organisation. Experienced staff collaborate to create new knowledge out of their shared expertise. Knowledge can easily be kept largely tacit. The engineers know the basics, and a short call to their colleagues fills in any gaps. The biggest risk is knowledge loss, as so many of the workforce will retire soon, and a Knowledge Retention strategy would be a good investment.

An organisation with many inexperienced staff

In many parts of the world, such as the BRIC countries, the economy is growing, the population is growing, there is a hunger for prosperity, and engineering (in contrast to the West) may be a growth area. The workforce in a growing organisation may be predominantly very young - many of them fewer than 2 years in post. There are only a handful of real experts, and a host of inexperienced staff - the red line in the chart above.

Experience is a rare commodity, and is centralised within the company, retained within the Centres of Excellence, and the small Expert groups. Here the issue is not Collaboration, but rapid onboarding and upskilling. The risk is not so much Retention of knowledge (although of course the knowledge of the few experts is vital and must be protected), but is more about deployment of knowledge. The reliance on a few experts means that they must be given a Knowledge Ownership role, rather than using them on projects. Rather than keeping knowledge tacit, it makes sense to at least document the basics in explicit form (the experts will be too busy to answer basic questions), though there is of course a need to keep this documentation updated as the organisation learns.

The KM framework

These two demographic profiles would lead you to take two different approaches to developing a KM framework. The first (experienced) company would introduce communities of practice, and use the dispersed knowledge to collaborate on building continuously improving practices, processes and products. Wikis could be used to harness the dispersed expertise. There would be huge potential for innovation, as people re-use and build on ideas from each other. Crowd sourcing, and "asking the audience" are excellent strategies for finding knowledge.

The second (largely inexperienced) company would focus on the development and deployment of standard practices and procedures, and on developing and deploying capability among the young workforce. The experts would build top-class training and educational material, and the focus would be on Communities of Learning rather than Communities of Practice. Innovation would be discouraged, until the staff had built enough experience to know which rules can be bent, and which must be adhered to. Crowdsourcing is not a good strategy, and the "wisdom of the experts" trumps the "wisdom of the crowd".

These two demographic profiles would lead you to take two different approaches to developing a KM framework. The first (experienced) company would introduce communities of practice, and use the dispersed knowledge to collaborate on building continuously improving practices, processes and products. Wikis could be used to harness the dispersed expertise. There would be huge potential for innovation, as people re-use and build on ideas from each other. Crowd sourcing, and "asking the audience" are excellent strategies for finding knowledge.

The second (largely inexperienced) company would focus on the development and deployment of standard practices and procedures, and on developing and deploying capability among the young workforce. The experts would build top-class training and educational material, and the focus would be on Communities of Learning rather than Communities of Practice. Innovation would be discouraged, until the staff had built enough experience to know which rules can be bent, and which must be adhered to. Crowdsourcing is not a good strategy, and the "wisdom of the experts" trumps the "wisdom of the crowd".

It would be a mistake for an organisation in the second category to copy a KM framework from an organisation in the first category, and vice versa.