Why do children go to school to learn, rather than staying home and reading books?

Why, if you have access to the best cookery books in the world, do you still need to take personal tuition if you want to be a cordon blue chef?

If you have a street map in the car, why would you ever need to stop and ask for directions?

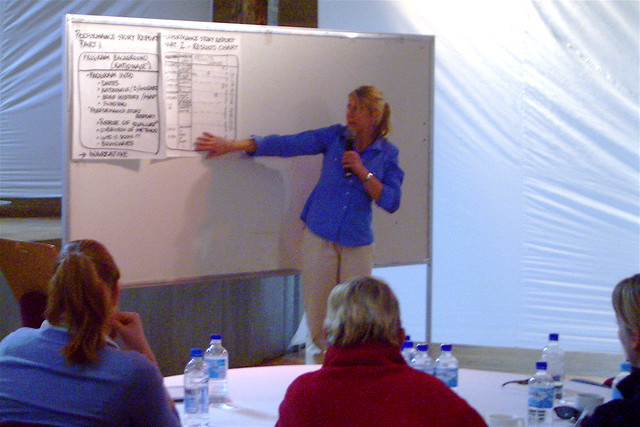

The answer, in every case, is that knowledge transfer is a social process, and if you want to transfer detailed knowledge you have to engage in conversation (specifically, in

dialogue) with other human beings.

Dialogue allows you to ask questions, seek clarification, test understanding, and look for that "aha" moment when the knowledge is really transferred. Dialogue allows access to the deep tacit knowledge - the knowledge that people don't even know that they know - and it allows you to check whether you are really understood the knowledge.

Any good teacher knows that discussion and dialogue in the class is far better at developing understanding than teaching by rote. Any cook knows there are tricks you can’t pick up from any book. Any driver knows that there comes a time when the map is not enough, and they need to wind down the window and ask a real human being with local knowledge.

Why is dialogue so important in Knowledge Management?

The majority of knowledge within any organization is held in people’s heads. Indeed some would claim that ALL the knowledge is in people’s heads, and that anything which is written down becomes information, rather than knowledge. However for the purposes of this article we will call written knowledge “explicit” and “head knowledge” will be referred to as “tacit” (although this is not the strict definition of the term).

There are two sorts of tacit knowledge in anyone’s head – the knowledge which they are conscious of, and the unconscious knowledge, the deep knowledge of which they are unaware. The matrix below identifies four states of knowledge, depending on whether the person has the knowledge or not, and whether they are conscious of it or not.

The bulk of the useful knowledge is likely to lie in the box of unconscious competence, where people who have gained the knowledge have not yet taken the time to analyse what they have learned, and make it conscious so it can be transferred to others.

Under these circumstances, the transfer of knowledge from one person to another is not an easy thing to achieve!

The person who has the knowledge (the "knowledge supplier") may only be partially conscious of how much they do know. The person who needs the knowledge (the "knowledge customer") may only be partially conscious of what they need to learn.

If we look at the matrix below, the knowledge supplier has both conscious and unconscious competence, and the knowledge customer has both conscious and unconscious incompetence. Also the knowledge supplier doesn't know what the customer needs, and the knowledge customer doesn't know what the supplier has.

Without dialogue we cannot overcome the boundaries of not knowing. (Tweet this)

Dialogue

is needed, in order to

- Help the knowledge supplier understand and

express what they know (moving from superficial knowledge to deep knowledge)

- Help the knowledge customer understand

what they need to learn

- Transfer the knowledge from supplier to

customer, and

- Check for understanding

The knowledge

customer can ask the knowledge supplier for details, and this questioning will

often lead them to analyse what they know and make it conscious. The knowledge supplier can tell the customer

all the things they need to know, so helping them to become conscious of their

lack of knowledge. As pieces of

knowledge are identified, the customer and supplier question each other until

they are sure that transfer has taken place.

What types of dialogue are there?

Although we have been talking here about knowledge transfer from one supplier to one customer, this will not always be the case. Usually the knowledge is held by more than one person – often by a team. (the team also has another specific role here, it helps define the contextual domain of why the knowledge may be valid to another team. One person has the personal context of “why this works for me”, the team can provide the more smoothed data that would appeal to a larger audience through the process of consensus) There may be many customers for the knowledge, and many different teams may need access to the knowledge at various times in future. Dialogue can take place within teams and between teams, as well as between individuals. However the processes and formats for the dialogue vary, depending on the number of customers, the number of suppliers, and whether the knowledge is being pushed or pulled.

The matrix below shows some of the forms that the dialogue may take, depending on whether the supplier and customer are one individual or team, or many individuals or teams.

Contact Knoco for guidance on how Dialogue can be part of your Knowledge Management Framework.

.jpg)