This week I would like to upcycle a series of blog posts from 5 years ago about "revolutionising the productivity of the knowledge worker" - a challenge set for us by Peter Drucker

| Image from wikimedia commons |

‘‘The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is similarly to increase the productivity of knowledge work and knowledge workers".

That is the big challenge to the Knowledge Managers of this world - to increase the productivity of knowledge workers by a factor of 50. The good news is that we are half way there. The bad news is that we have a long way still to go.

I already provided a summary of this task in a previous blog post, but would like to amplify, here and over the next few days, on the four factors which we, as Knowledge Managers, can influence. And the first of these is the division of knowledge labour.

The division of labour was a huge step in improving manual worker productivity. This involved dividing manual work into tasks, as in an assembly line process, and the recognition that the manual worker did not need to make everything. They would have their task, work on their component, and others would make the rest.

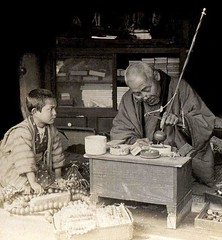

My grandfather was a village blacksmith. He was a craftsman - he could make a set of wrought-iron gates, for example, which were a work of art. He would start with iron bars, and do all the work himself. The result was excellent quality, but it took a very very long time.

Nowadays iron gates are made in a factory. The quality may be less (though they are definitely fit for purpose, and in some cases factory quality is better than craftsman quality), but the cost is far less, and the productiviy is massively higher.

As Wikipedia says, referring to Adam Smith's famous example of the pin factory -

The manual worker equivalent

The division of labour was a huge step in improving manual worker productivity. This involved dividing manual work into tasks, as in an assembly line process, and the recognition that the manual worker did not need to make everything. They would have their task, work on their component, and others would make the rest.My grandfather was a village blacksmith. He was a craftsman - he could make a set of wrought-iron gates, for example, which were a work of art. He would start with iron bars, and do all the work himself. The result was excellent quality, but it took a very very long time.

Nowadays iron gates are made in a factory. The quality may be less (though they are definitely fit for purpose, and in some cases factory quality is better than craftsman quality), but the cost is far less, and the productiviy is massively higher.

As Wikipedia says, referring to Adam Smith's famous example of the pin factory -

"Previously, in a society where production was dominated by handcrafted goods, one man would perform all the activities required during the production process, while Smith described how the work was divided into a set of simple tasks, which would be performed by specialized workers. The result of labor division in Smith’s example resulted in productivity increasing by 24,000 percent (sic), i.e. that the same number of workers made 240 times as many pins as they had been producing before the introduction of labor division"

Division of knowledge labour

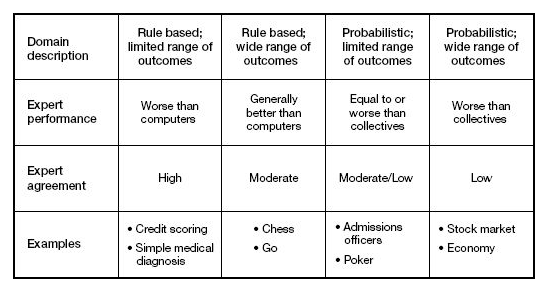

The knowledge equivalent of a craftsman is an expert. Much as a craftsman such as my grandfather would make the whole object himself, from raw materials, so an expert would hold all the knowledge in their head, from first principles to the final decision. Many decades ago, if you needed knowledge to be applied, you called the expert. You got good results, the quality of decisions was good, but it may take a long time to find and deploy the expert.Just as the transition from a craftsman economy to a manufacturing economy involves the division of labour, so different people make different parts, so the transition from an expert economy to a knowledge economy involves the division of knowledge, so that different people know different parts.

The division of knowledge is the recognition that knowledge can be more effectively deployed and managed within a community or network, rather than held by an expert, and the division of knowledge work is the effective use of networked knowledge workers. Leaving knowledge in expert heads is seen as inefficient and ineffective.

In many organisations, this shift has happened. Knowledge work has become divided - people know as much as they need to know and no more, confident that they can find any extra knowledge when needed. Juniors perform tasks, with the help of KM, which in the past were the domain of experts. New hires answer customer queries, junior GPs address topics that used to be the purview of specialists, young lawyers do the work that partners used to do. From being the "font of all knowledge," the experts become the "stewards of knowledge" on behalf of the community.

Division of intellectual labour is "work in progress" for KM - a movement that has started, but maybe can develop even further. By dividing the knowledge work, we avoid the need to rely on experts for every decisions, and massively improve the productivity of the knowledge workers, provided they have access to the knowledge needed for their component of knowledge work. How that knowledge is provided will be covered in tomorrow's post.