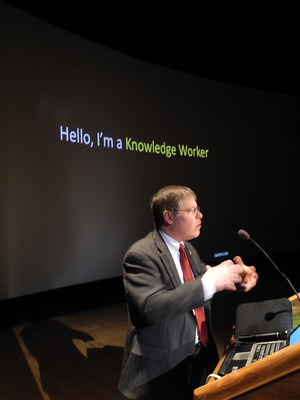

If leaders are to empower their knowledge workers, they have to let go of "always having the answer"

|

| Image from wikimedia commons |

The book "It's Your Ship: Management Techniques from the Best Damn Ship in the Navy" tells how Captain Michael Abrashoff took command of the USS Benfold and turned it from being the worst performing ship in the fleet, to the best.

One key factor he mentions is familiar to all of those wishing to instil a Knowledge Management culture, and that is the willingness of leaders to let go of the "need to know all the answers", and to start to make use of the knowledge of the organisation.

As Abrashoff says

This empowerment, and this leadership move from being a Knower to being a Learner, are components of the culture shift that KM brings about, and which in turn liberates the knowledge, and also the performance, of the whole organisation. This cultural shift may be harder in some national cultures than others. However the message is clear -

"Officers are told to delegate authority and empower subordinates, but in reality they are expected never to utter the words “I don’t know.” So they are on constant alert, riding herd on every detail. In short, the system rewards micromanagement by superiors— at the cost of disempowering those below.....

"I began with the idea that there is always a better way to do things, and that, contrary to tradition, the crew’s insights might be more profound than even the captain’s. Accordingly, we spent several months analyzing every process on the ship. I asked everyone, “Is there a better way to do what you do?” Time after time, the answer was yes, and many of the answers were revelations to me.

"My second assumption was that the secret to lasting change is to implement processes that people will enjoy carrying out. To that end, I focused my leadership efforts on encouraging people not only to find better ways to do their jobs, but also to have fun as they did them".

What Abrashoff discovered was the difference between managing knowledge workers, and managing manual labourers. Knowledge workers generally know more about their work than their boss does. They use knowledge to make decisions and take actions on a daily basis, and they know what works and what doesn't. The manager's role is not to be the arbiter of those decisions, even less to be the decision maker, but to empower and enable the knowledge workers with the tools they need to get the right knowledge to make the right decision. Often the right response from the leader is "I don't know the answer - why don't you go find out what others do, and learn from them".