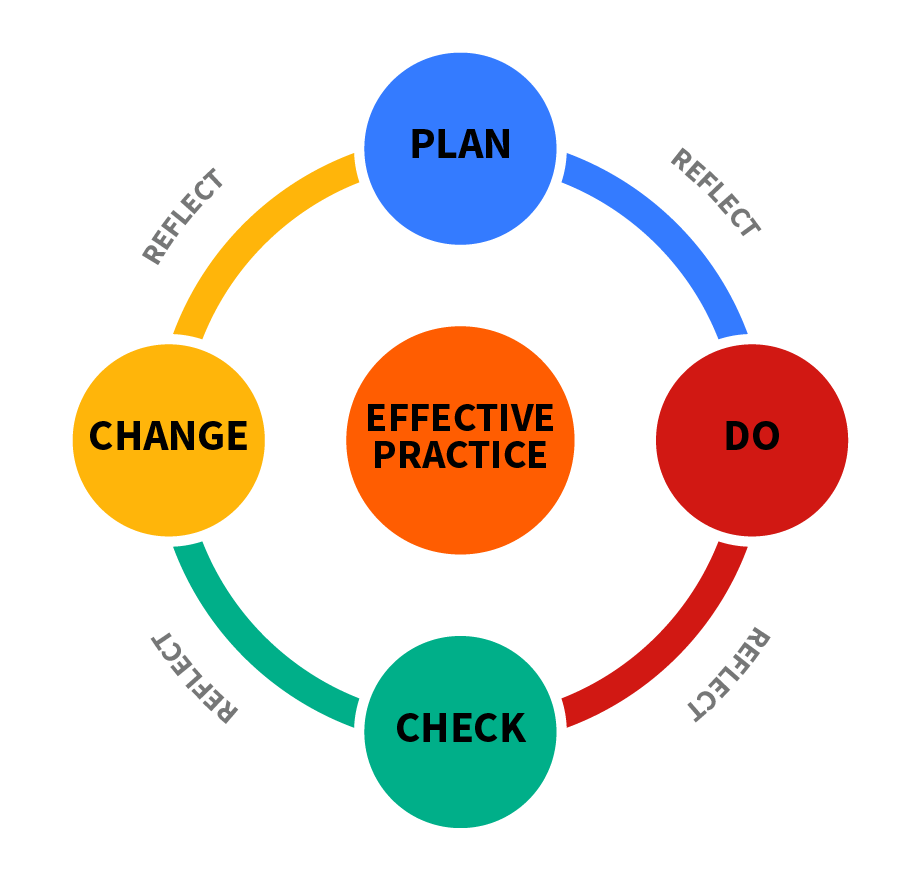

Knowledge is born in a three-stage process of reflection on experience; from observations, through insights, to lessons.

I think most people accept that knowledge is born through reflection on experience. The three-stage process in which this happens is the core of how the military approach learning from experience, for example as documented in this presentation from the Australian Army (slide 12).

The three stages are the identification of Observations, Insights and Lessons, collectively referred to as OILs. Here are the stages, using some of the Australian Army explanation, and some of my own.

- Observations. Observations are what we capture from sources, whether they be people or things or data or information or events. Observations are "What actually happened" and are often compared to "What was supposed to happen" (the gap between "Supposed" and "Actual" is a gap of Surprise, which is the first sign that there is new knowledge to be found). Observations are the basic building blocks for knowledge but they often offer very limited or biased perspective on their own. However storing observations is at least one step better that storing what was planned to happen (see here). For observations to be a valid first step they need to be the truth, the whole truth (which usually comes from multiple perspectives) and nothing but the truth (which usually requires some degree of validation against other observations and against hard data).

- Insights. Insights are conclusions drawn from patterns we find looking at groups of observations, or from analysis of a single observation. They identify WHY things happened the way they did, and insights come from identifying root causes. You may need to ask the 5 whys in order to get to the root cause. Insights are a really good step towards knowledge due to their objectivity. The Australian Army suggests that for the standard soldier, insights may be as good as lessons.

- Lessons. These are the inferences from insights, and the recommendations for the future. Lessons are actionable knowledge which has been formulated as advice for others, and the creation of lessons from insights requires analysis and generalisation to make the insights specific and actionable . The Australian army defines lessons as "insights that have specific authorised actions attached.... directed to Army authorities to implement the stated action", and there is a close link between defining an actionable lesson, and assigning an action to that lesson. Note however that the lesson is not "Learned" until the action is taken, and sustainable change has been made.

In other organisations these three stages are separated. Perhaps observations are collected by (for example) users, a separate team of analysts use these observations to derive insights, and then an authoritative body adds the action and turns the insights into lessons.

My personal preference is to address all three steps as close as possible to the activity which is being reviewed, using the same team who conducted the action to take Observations through to Lessons.