If you read through a lessons learned database from a British, US or Australian organisation, you get the feeling that projects never go right. The database will be full of lessons from failure, with almost no success-based lessons.

If you read through a lessons learned database from a British, US or Australian organisation, you get the feeling that projects never go right. The database will be full of lessons from failure, with almost no success-based lessons.If you read through a lessons learned database from a Middle Eastern or Far Eastern organisation, you get the feeling that projects never go wrong. The database will be full of lessons from success, with almost no failure-based lessons.

OK, the statements above are generalisations and your particular company may differ, but there is a reality behind them representing two different biases; in the first case, the bias against "showing off to your peers"; in the second case, the bias against "appearing to have failed in front of your manager".

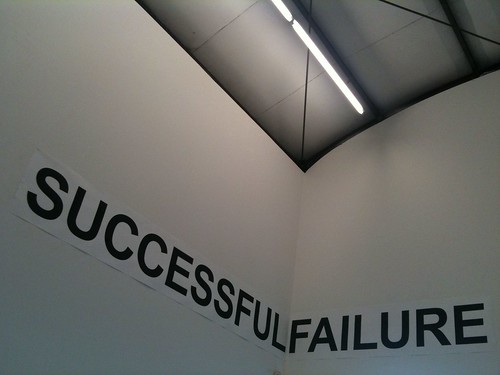

In reality, of course, we need to learn from both success and failure, particularity when these are unexpected. We need to seize on, and repeat, the breakthroughs, and map out and eliminate the pitfalls.

As far as the user of the lessons is concerned, they don't actually care whether the lesson came from success or failure, so long as

a) it is well written,

b) they trust the provenance, and

c) it helps them deliver their own project better, cheaper, faster.

In both the case of failure and success, the lesson will be written in the same way; a set of recommendations and advice, supported by context (in the form of a story) which helps them internalise the lesson.

2 comments:

Sorry but I'm struggling with this one...a lesson is generally considered 'learned' when the desired change in behavior has occurred. You don't change something because it is working/optimal: you change it because it is not. Therefore someone further back down the timeline, something not been working or has become suboptimal and has needed to be changed. If you do not track and record the original catalyst from which the lesson was ultimately derived, and only herald the successful implementation, then you run the very real risk of forgetting why you made the change.

Failure might be a little strong though: the greatest catalyst for change is a good punch in the nose i.e. pain is a great motivator. I think that you would be hard-pressed to find too many effective lessons that did not have a grounding in some for of organisational pain or sub-optimal performance. Happy to be proven wrong or to hammer out over some virtual ales...

Lessons can some through breakthroughs or through pitfalls, and both of these help define the optimal ways of doing things. Processes and behaviours change when someone finds a better way. A great example is high-jumping (see the blog post here - ). Nowadays everyone does some sort of variation on the Fosbury Flop, because that was a successful breakthrough form which others learned.

Do we need to record the catalyst for this breakthrough (other than immortalising Dick Fosbury's surname)? Do we need to record the people who failed? Or do we follow the winners? The effective lesson, for high-jumpers, is learning from the winning technique.

Post a Comment