If we view the flow of knowledge within an organisation as a Market, then we need to address the issues of supply and demand, and there are many advantages to starting by stimulating demand.

We can look at the flow of knowledge within an organisation as a market connecting the suppliers of knowledge and users of knowledge; the people in whose minds the knowledge is buried, and the people and teams who need access to that knowledge.

Knowledge is created through experience and through the reflection on experience, in order to derive guidelines, rules, theories, heuristics and doctrines. Knowledge may be created by individuals, through reflecting on their own experience, or it may be created by teams reflecting on team experience. It may also be created by experts or communities of practice reflecting on the experience of many individuals and teams across an organisation. The individuals, teams and communities who do this reflecting can be considered as ‘knowledge suppliers’.

Knowledge is applied within organisational activity by individuals and teams. They can apply their own personal knowledge and experience, or they can look elsewhere for knowledge – to learn before they start. The more knowledgeable they are at the start of the activity or project, the more likely they are to avoid mistakes, repeat good practice, and avoid risk. These people are ‘knowledge users’.

Once we have knowledge suppliers and users, we have a marketplace for knowledge, where suppliers and users come together and exchange a "commodity" - knowledge. Knowledge is not like a normal commodity in that the supplier does not lose the knowledge, and both supplier and user get to keep the knowledge which has been exchanged. However a marketplace analogy is a popular one in KM terms, and its an analogy I would like to explore here.

A marketplace works when there is supply and demand - suppliers and users. Supply and demand is at the base of much economic theory, and the concept of an equilibrium market as applied to normal products is that supply and demand will match each other through the mechanism of price adjustment. When supply and demand are out of synch, then prices adjust as follows:

- When demand exceeds supply there is a shortage in the market and prices rise until demand decreases

- When supply exceeds demand, there is a glut in the market and prices fall until demand increases.

We see this very clearly in the oil markets. When oil supply falters, prices skyrocket. When oil production picks up, for example through the advent of shale-oil, prices fall.

This relationship works with established commodities - any new product will create its own demand, at least for a while. There was no market for mp3 players before they were invented, and no market for Rubik's cubes or Pokemon until it was stimulated by supply of these new playthings. After a while this "fad effect" wears off, and companies seek to stimulate continued demand through marketing and advertising in order to keep prices high.

The Knowledge Market

In a Knowledge market there is no monetary price payable for knowledge, at least not within any one organisation. The price that a user pays for knowledge is the degree of effort they will put in to get it, and the amount of searching, filtering, asking and browsing they are prepared to do.

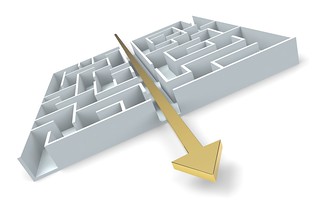

The diagram above shows four potential states for the Knowledge Market within an organisation.

- Where there is low supply and low demand, there is no knowledge market.

- Where there high supply and high demand, there is an equilibrium knowledge market, and to reach this level should be the Knowledge manager's goal.

- Where there is high supply and low demand, we find the typical problem area of knowledge oversupply. Here we find the huge databases nobody ever reads, the massive lessons learned systems with no lessons re-use, the communities or social groups where announcements and notifications outweigh the questions. The effect of this oversupply is both to introduce waste into the system, and also to destroy value. Larry Prusak said that the best way to de-knowledge knowledge is through oversupply. Oversupply would not be problem if the price/cost of the knowledge dropped to compensate, but in fact the opposite happens. The more you oversupply knowledge, the more time and effort it costs to search, sift and sort through until you find the knowledge you need. Oversupply increases cost and decreases demand even further.

- Where there is low supply and high demand, we find the less typical problem area of knowledge undersupply. Here we find lots of people looking for knowledge, but little knowledge to find. The effect of this undersupply is to make people look harder, and to seek for knowledge even if it is not yet documented. They start asking people, talking to people, and eventually finding knowledge in its richest state - tacit knowledge. What documented knowledge exists becomes highly valued.

The route to equilibrium

The instinct for many Knowledge Managers is to create an equilibrium Knowledge Market by stimulating supply, for example by capturing knowledge, rewarding knowledge publishing, creating databases, promoting "knowledge sharing", or "working out loud".

Unfortunately stimulating supply without stimulating demand leads straight into the issue of knowledge oversupply, and once this issue has arisen and knowledge has been devalued as a result, it can be very hard to escape.

Better to take the green arrow in the diagram above, and start by stimulating demand for knowledge. You do this by asking management to set the expectation that people and projects will learn before doing, and by promoting knowledge gap analysis, peer assists, question-driven communities of practice, and "knowledge seeking". Better to have the seekers outnumber the sharers, and to watch the value of knowledge rise as the seekers find what they need, apply it, and gain value as a result.

Begining by stimulating demand avoids the common pitfall of the knowledge glut and a devaluation of knowledge.

.png)