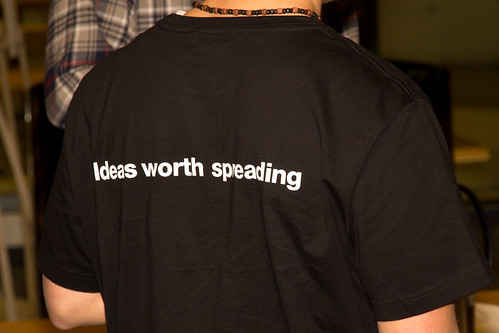

Sharing is no guarantee of uptake. Sometimes better practices and innovations take a long time, and require a lot of support, to take hold.

Here is a very interesting article from the New Yorker, by Atul Gwande, about why some ideas or best practices catch on and spread, while others don't. In today's connected world we expect good ideas to diffuse virally, but the fact is that many great ideas never spread.

Here is a very interesting article from the New Yorker, by Atul Gwande, about why some ideas or best practices catch on and spread, while others don't. In today's connected world we expect good ideas to diffuse virally, but the fact is that many great ideas never spread.For example, Gwande contrasts the histories of anaesthesia and asepsis in medicine - both important life-saving ideas, but the practice of anaesthesia spread like wildfire, while asepsis is still not properly adopted world wide. What was the difference between the two?

The difference was the immediacy and visibility of the problem to the practitioner.

Anaesthesia solved an immediate and visible problem for the surgeon. Under ether, the patient was no longer screaming and thrashing about, and the operation could take place in peace and quiet. Asepsis, on the other hand, did not solve an immediate problem. The operation took place as normal, and nothing apparently changed. As far as the surgeon could see, there was no immediate improvement. OK, the long term patient survival rate improved with asepsis, but that was a longer term issue and more remote for the surgeon. Asepsis solved a big problem, but a problem that was largely invisible to the practitioner, at least in the short term.

Gawande concludes that with the big invisible problems, you cannot expect improved practices to spread virally. You need to work on them. You need to sell the solutions, and like sales reps, that requires frequent interactions (the "seven touches") between the trainer or knowledge holder and the user - person to person, door to door, talking.

He gives an example of an interaction with a nurse who learned, from a visiting trainer, a new practice that improved the survival rate of newborn infants. This was a practice that addressed one of these "invisible problems", but had proved very difficult to spread. Gwande wanted to know why the nurse had adopted the practice in this case.

“She showed me how to get things done practically,” the nurse said.

“Why did you listen to her?” I asked. “She had only a fraction of your experience.”

In the beginning, she didn't, the nurse admitted. “The first day she came, I felt the workload on my head was increasing.” From the second time, however, the nurse began feeling better about the visits. She even began looking forward to them.

“Why?” I asked. All the nurse could think to say was “She was nice.”

“She was nice?” “She smiled a lot.” “That was it?”

“It wasn't like talking to someone who was trying to find mistakes,” she said. “It was like talking to a friend.”This was one of those big ideas that spread through repeated personal contact and influence, rather than virally, and the repeat contact and trust that developed between the trainer and the nurse was vital for adoption and re-use of the knowledge.

So what is the implication for Knowledge Management?

The implication comes through the strategies you need to employ for knowledge re-use. Where knowledge solves an immediate problem for the user, then you can rely on a viral approach. Where it solves a longer term problem for the organisation, but may be invisible to the user, then knowledge re-use needs to be promoted through training, coaching and frequent interaction with a friendly person.

No comments:

Post a Comment